How rare is a palindromic day? (回文日期)

Today is a special day called “palindromic day”, as you may have seen in the news. A palindromic day is a day, whose date, when written in certain forms, is a palindromic number.

We start with the definition of palindromic numbers from Wiki

“A palindromic number is a number that remains the same when its digits are reversed”.

Thus, 1221 or 12221 are both palindromic numbers. Those numbers also have a mirror/reflection symmetry in the sense that they have a symmetric center “12$\vert$21” or “12$\vert$2$\vert$21”. This leads to the observation that if a number has odd numbers of digits, its symmetric center can ba arbitrary “12$\vert$n$\vert$21”.

When it comes to days, the situation becomes more complicated as people have different conventions in recording dates. In the following, we use “YYYY”, “MM” and “DD” to denote year, month and day. In general, there are three different forms, “YYYY-MM-DD”, “DD-MM-YYYY” and “MM-DD-YYYY”. Thus, today is a global palindromic day, meaning the date is a palindromic number in anyone of the above forms. This is of course, very rare and the previous one comes at 1111-11-11, about 909 years ago. Now, let’s release the constraint and consider only ISO 8601 standard form “YYYY-MM-DD” to see how rare a palindromic day could be?

If we consider year from 1 to 2020, there are less than 10^6 days. So, we can first use a program to help us to select the palindromic numbers. For such a small state space, we do not really need any pruning so I simply search with brute force.

1 | Year = Table[yr, {yr, 1, 2030}]; |

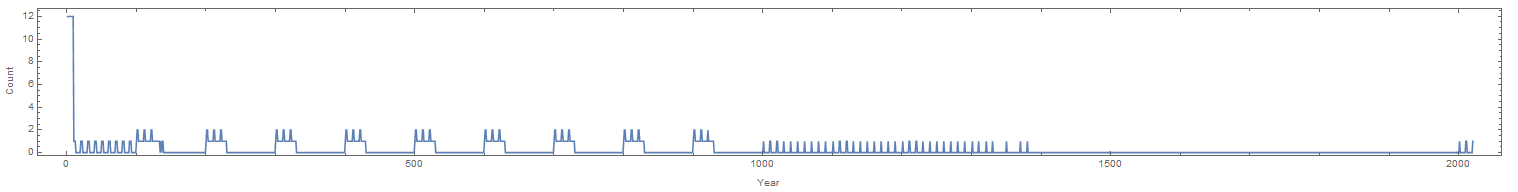

This is the Mathematica program I used to search for the dates and it returns the plot shown above (view in a new window to see the entire plot). The program is fairly easy and I don’t explain it here. The most striking feature of the final plot is that it shows certain beat patterns, namely, there’re some orders in palindromic days over the past thousands of years!

To take a closer look at the date, we split the days into 4 groups, “Y-MM-DD”, “YY-MM-DD”, “YYY-MM-DD” and “YYYY-MM-DD”, corresponding to years 1-9, 10-99, 100-999 and 1000-2020. We note that the pattern changes within each group. For the first group, we can count the total of palindromic days using

1 | Select[Sort@ToExpression@SymDate, # <= 99999 &] |

which turns out to be 108. If we look at the beat pattern, we would find that it as 12 palindromic days in each year. This is easy to understand as each month has a palindromic day on xth for a given year x. When it comes to year 10-99, the total would much less since it has an even number of digits. It can be counted as (9)(3)=27 because for each digital x=1-9, we have x0-11-0x, x1-11-1x and x2-11-2x satisfy the requirements. Note that all those days happened in November and now we understand how those beat patterns form.

Applying similar counting processes (yet way more complicated), we could find the total of palindromic day for the other two groups, which are summarized in the following table, with their frequencies in the given time frame.

| Year | 1-9 | 10-99 | 100-999 | 1000-2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 108 | 27 | 330 | 49 |

| Percent | 1200% | 30.34% | 36.71% | 4.80% |

Finally, the next palindromic day is 2021-12-02, happening next year. Following that it’s 2030-03-02, which will be 10 year from now. So, palindromic day is indeed rare for our generation.

Reference

How rare is a palindromic day? (回文日期)

https://blog.qisland.org/2020/02/02/2020-2-2-Palindromic-day/