Beyond mean field theory: the renormalization group idea

This is my term paper for PHYS $5313.001$ - Statistical Physics - S$17$.

Abstract

In the class, we already study the phase transition in Ising model using mean field approximation and correspondingly examine its validity, where we find that mean field theory (MFT) actually breaks down when $$T\sim T_c$$ and $d < 4$ both hold. In other word, when the correlation length is sufficiently large, we have to properly take fluctuation into account. This requires a brand new way of thinking, that is, the renormalization group (RG) idea. In this term paper, we study those two different recipes, mainly used in modern physics to describe phase transitions and critical behaviors, on the ground of the materials discussed in the class. We extend our discussion to correlation functions and more critical exponentials. Again, we incorporate Ising model to present how those two theories (ideas) work. The main contents come from the textbooks.

Introduction and background

Materials may exhibit diverse functionalities depending on its constituents and external elements. Meanwhile, if one equally divides a given piece of material into two parts, the macroscopic properties such as density or magnetization, of this material should remain the same. However, this fails when one repeats the operations for many times. There exists a so-called correlation length, at which, the overall properties of one piece start to differ significantly from those of the original.

In most common materials, we expect to have the correlation length in the order of few interatomic distances. This provides us with the convenience that even a small region of atoms (or molecules) should give a decent approximation. Nevertheless, correlation also can be affected by some external conditions like temperature, electromagnetic fields and pressure. The fact that some macroscopic properties may undergo a sudden change even when those external parameters vary smoothly actually marks a procedure we called phase transition. One possible form of phase transition is that there are multiple states on either sides around the critical point. At the critical point, all the state may co-exist, however, even slight deviation from the critical point will give an unique phase. Such that, we should be able to identify abrupt changes for some thermodynamic quantities when pass through proper region in parametric space. This is what we referred to as first-order phase transition. Generally, in a first-order transition process, the correlation length should remain finite.

Another type of transition we would like to mention is continuous transition, where the correlation length is effectively infinite and consequently, the fluctuations are correlated over all length scale. In such transition procedure, different phases must become identical when the critical point is approached. Unlike first-order transition, which can be described by traditional perturbative in most cases, continuous phase transition is much more difficult to attack in the sense that an infinite correlation length brings too many degree of freedoms together. Renormalization group (RG) idea is introduced to solve such a strongly coupled system.

Even though such a system is extremely complicated, some universalities have been identified in it. Near the critical point, many thermodynamic properties and even the correlation length show some power-law behaviors. More interesting, those powers (critical exponents) are only determined by, instead of the characteristic properties of the system, more generally physical features like symmetries of the Hamiltonian or the spatial dimensions. As a matter of fact, this exponential expressions are closely connected to both RG and scaling behavior.

In this context, we mostly consider two widely used methods, mean field theory (MFT) and RG to describe phase transitions. We still incorporate the Ising model to start our discussion to be consistent with what we did in the class. Here, we hope to capture the essential ideas behind those two schemes by investigating the thermodynamic properties (free energy), critical exponents and correlation function.

Although simple, Ising model is one of the most useful systems in statistical mechanics. Lower dimensional models can be exactly solved with some mathematical tricks, for example, using Pauli operators transformation to solve 1D Ising model with a transverse filed. A $2$D system can also be calculated exactly through some endeavors. Here, we will not go through the details about how to solve this model, instead, what we want is using minimal computing to extract maximal physics.

The Ising model describe a system composed of $N$ classical spins $s(r) =\pm 1$ for each lattice site $r$ of a $d$-dimensional spin. Then, one may write down the Hamiltonian as $H = - \frac{1}{2} \sum_{r,r’} J(r - r’)s(r)s(r’)+b\sum_rs(r)$, where $J(r - r’)$ is the coupling strength of two spins, $b$ represents some external parameter (most commonly magnetic field) and the extra factor $\frac{1}{2}$ is due to over-count of pair $(r, r’)$ and $(r’, r)$.

We assume the readers are already familiar with the basic knowledge, for example, ferromagnet-paramagnet transition, critical temperature, etc., in this question. In this term paper, there are five critical exponential (including correlation length) we would like to discuss here:

i) The specific heat when no external fields presenting, $C \sim A\vert t\vert^{-\alpha}$,

ii) The spontaneous magnetization due to interaction $M_0=\lim_{H\to0+} M \sim (-t)^\beta$,

iii) Susceptibility in zero field $\chi = \frac{\partial M}{\partial H}\vert_{H=0} \sim \vert t\vert^{-\gamma}$, where $t=(T-T_c)/T_c$ is the normalized temperature,

iv) The magnetization near critical point with non-zero magnetic field $M \sim \vert H/k_bT_c\vert^{1/\delta}$,

v) A quantitative measurement of correlation length $\xi$ can be given by the asymptotic behavior ($\xi \ll r$)of the correlation function $G(r) \sim e^{r/\xi}/r^{(d-1)/2}$, where $\xi$ is introduced as $\xi^2 = \sum_r r^2G(r)/\sum_rG(r)$.

Mean field approaches

First, we embark the mean field theory to study this model, starting from its thermodynamics. The partition function of the system is

$Z = \text{Tr} \left( e^{\frac{\beta}{2} \sum_{r,r’} J(r - r’)s(r)s(r’)+\beta H \sum_rs(r)} \right)$,

where we have replaced $b$ with $H$ to indicate a uniform magnetic field and $\beta = 1/k_BT$ as usual. The model becomes trivial if we put the exchange coupling $J(r-r’)=0$ and one may calculate the magnetization $\langle s \rangle =\tanh (\beta H)$ as illustrated in any textbook.

The main idea of mean field theory is quite simple and straightforward, using single particle partition function to approximate the interacting case. This requires us to linearize the square term appeared in exchange coupling. Meanwhile, in this case, we already know that $H$ will give a non-zero magnetization $M=\langle s \rangle$ and it will survive (in ferromagnetic phase) even one turns the magnetic filed off. With those hints, we linearize the quadratic term using $s(r) = M + \left( s(r) - M\right)$ and only keep the first or lower order terms with respect to $\delta s(r)=s(r)-M$

$s(r)s(r’)= M\left(s(r)+s(r’)\right) - M^2 + O\left((\delta s(r))^2\right)$.

What we neglected here actually represents the interaction between spins at different sites, in this sense, we expect that mean field approximation only works when this interaction is relatively weak, that is, the correlation length is quite small. As we already did this in class, I will not go to details at this moment. Another useful result we derived in class is

$f = a + b t M^2 + c M^4 + d H M$,

where $a$, $b$, $c$ and $d$ are just constants and $t$ is the normalized temperature $t = (T-T_c)/T_c$.

Surprisingly, even this simple relation can give us sufficient knowledge about the listed critical exponentials. First, when $H = 0$ and $t < 0$, $f’(M_0) = 0$ gives $M_0 \sim (-\frac{b}{2c}t)^{1/2}$. One may readily conclude $\beta=\frac{1}{2}$. Similarly, we have $M\sim cH/at$ for $t>0$ giving $\gamma = 1$ (note that $\chi\sim M$) and $M\sim (cH/b)^{1/3}$ when $t=0$ indicating $\delta=3$. For the specific heat, we need to study both situations. First, when $t<0$, $f$ has one minimum $a$ located at $M=0$. On the other hand, $f$ has two minima of order $a + O((bt)^2/c)$ at $\pm M_0$ when $t<0$. This gives rise to the discontinuity of specific heat at $t=0$ and, as a matter of fact, can be directly ascribed to the fact that we did not account correctly for fluctuations in mean field theory. Nonetheless, we are safe to conclude $\alpha = 0$.

Even though we have used a somewhat coarse approach, it still provides us with the first glance at universality. All the critical potentials seem to be independent of any detail of the system and are only determined by the mathematical expression of free energy, that is, the dependence of free energy $f$ on order parameters $H$ and $M$. Taking a further step, we notice that symmetry is implicitly used when we write down the free energy (spin reversal symmetry in this case). So, here, we study the problem from a more general situation. Assuming we have $n$ order parameter $M_i$ with $O(n)$ symmetry, a direct generalization of the free energy we discussed above takes the form

$f = a + b t \sum_i M_i^2 + c \left( \sum_i M_i^2\right)^2 + \text{higher-order terms}$.

The minimum $M_0 = \left( (-bt/2c)^{1/2}, 0, … \right)$ is fixed by the spontaneous symmetry break of $O(n)$ when $t<0$, and again, we expand $f$ at $M_0$ to the second order

$f = f_0 + 2 b \vert t\vert m_1^2$,

where $m = M - M_0$. Only the modes $m_1$ remains finite while all other modes have effectively infinite correlation length and thus, decay as power laws. However, this is caused by symmetry break, not neglecting fluctuations.

Since most thermodynamic properties and critical exponentials can be extracted from free energy, which can be expressed according to symmetry of order parameters. Now, we turn to use mean field approximation to study the correlation function to get the last critical exponential of interest, which has been calculated so far, the correlation length. The two-point spin-spin correlation function in high temperature region without external field is

$$\begin{align} G(r,r’) &= \langle s(r) s(r’)\rangle \ &= \frac{\text{Tr} s(r)s(r’)e^{\beta/2\sum_{q,q’}J(q-q’)s(q)s(q’) }}{\text{Tr} e^{\beta/2\sum_{q,q’} (q-q’)s(q)s(q’) }}. \end{align} $$

To simplify this function, we first set $r’=0$ without loss of any generality, and note that $\delta_{s(0),1}+\delta_{s(0),-1}=1$, we have

$G(r) = \frac{\text{Tr’} s(r)e^{\beta/2\sum_{q,q’}J(q-q’)s(q)s(q’) }}{\text{Tr’} e^{\beta/2\sum_{q,q’}J(q-q’)s(q)s(q’) }} = M(r),$

where Tr’ represents taking trace over all spins expect $s(r)$ and $M(r)$ is just the magnetization at $r$ when the original is set to be $s(r)=1$. Now, if we apply mean field approximation as before and minimize the free energy, we obtain

$G(r) = M(r) = \tanh \beta \left( \sum_{r’} J(r-r’) M(r’) \right)$.

It’s difficult to solve this equation, but if we take the large $r$ and small

$M$ approximation, we can solve it in k-space analytically using Taylor expansion

$G(k) \sim \frac{R^{-2}}{k^2 + \xi^2}$,

where $R^2 = \sum_rr^2J(r)/\sum_rJ(r)$ and $\xi = Rt^{-1/2}$. Setting $k=0$ gives the susceptibility $G(0) \sim t^{-1}$, which is consistent with $\gamma=1$ we conclude in previous discussion. Now, transferring back to real space, $G(r) \sim e^{-r/\xi}/r^{(d-1)/2}$, this indicates that we can treat $\xi \sim t^{-1/2}$ as the correlation length. In fact, this correlation function can give us more information about other critical exponentials, however, we limit ourself to the aforementioned ones in this term paper. Since mean field theory relies on the assumption that $\sum_{r’}J(r-r’)\delta s(r)\delta s(r’)$ is negligible comparing to the energy of the system, and, with the knowledge of correlation function, we may test its validity from $\sum_{r’}J(r-r’)\delta s(r)\delta s(r’) \approx J\sum_{r’} G(r-r’)$. Nevertheless, as we already know the answer from class, I will skip this topic.

Renormalization group idea

To avoid prolix description, we start from one-dimensional Ising model with no Zeeman field to illustrate the basic idea of RG. The original idea “scaling” is suggested by L. Kadanoff\cite{Kadanoff1966} to put neighbor real spins into a spin block and then, study the block system. The spin of each block is determined by counting the vote of only the center spins, that is $T(s’;s_1,s_2,s_3) = \delta_{s’,s_2}$, where three real spins $s_1$, $s_2$ and $s_3$ are put in a spin block $s’$ and the vote is solely counted by the mid spin $s_2$. Such decimation process means our theory should only work at low temperature when all the spin in a block tend to have the same orientation. At first, we take a close look at two spin block within such a block spin system $s_1’(s_1,s_2,s_3)=s_2$ and $s_2’(s_4,s_5,s_6)=s_5$. Since it is a 1D system, we only need to take summation on the neighboring spins in different block, which gives the partition function as

$Z_0’ = e^{Js_1’s_3}e^{Js_3s_4}e^{Js_4s_2’}.$

Note that, we have absorbed $\beta$ into the coupling constant $J$. This can be further simplified using $e^{Js_3s_4}=\cosh J(1+s_3s_4\tanh J)$ and taking sum over $s_3$, $s_4$

$Z_0’=2^2 (\cosh J)^3 (1+x^3s_1’s_2’). $

To invert this into the Boltzmann factor $e^{J’s_1’s_2’}$, one finds

$Z_0’=e^{\tanh^{-1} \left( \tanh^3 J\right) s_1’ s_2’}$

Now, we are able to write the partition function of the whole system in the

usual way $Z = \text{Tr}’ e^{-H’(s’)}$ with the Hamiltonian

$H’(s’) = N’ g(J) - J’\sum_i s_i’s_{i+1}’.$

This $g(J)$ comes from short wave degrees of freedom and it only

bring some constant for the free energy, thus, will be neglected.

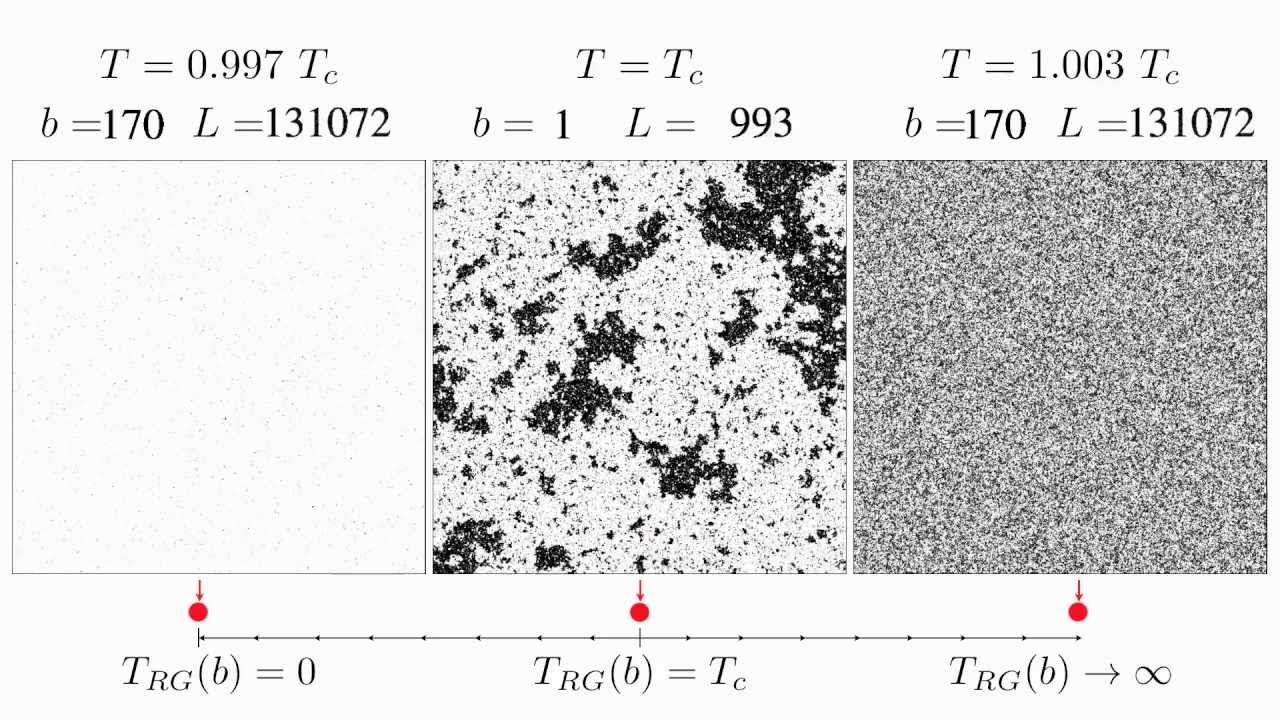

The essential part of the RG process is $\tanh J’ = \tanh^3 J$, for convenience, we denote $x = \tanh J$ and $x’ = \tanh J’$. Note that, $x \to 0+$ at high temperature and $x \to 1-$ at low temperature. We call these two limits fixed points, as $x$ is invariant when two limits are taken exactly. However, any deviation will render $x$ goes to $0+$. In this sense, we may consider there is a so-called RG flow from $x=1-$ (unstable fixed-point with $J=\inf$) to $x=0+$ (stable fixed-point with $J=0$). This gives a very important insight into this model, that is, in a short-range Ising model, it cannot be in an ordered state when $T > 0$, and correspondingly, no phase transition can take place. This means, in principle, we cannot extract any information about critical exponentials like $\alpha$ or $\gamma$. Nevertheless, the power of RG exhibits itself through the fact that we may still study the correlation length $\xi$. If one takes the lattice constant $a$ to be unit of length, $\xi$ should only be a function of $J$. The RG transformation preserves long-range physics like the correlation length $\xi(x)$, however, the lattice spacing is changed as $a \to ab$ (in above case, b=3). Combing those two facts, one may conclude $\xi(x’) = b^{-1} \xi{x}$ as it is easy to generalize to the case $x’ = x^b$ under rescaling factor $b$. This can be solved as

$\xi(x) = \frac{c}{\ln x},$

where $c$ is some constant and the asymptotic behavior of correlation length is $\xi \sim e^{1/T}$ when $T \to 0$. Following the same steps, one can apply the same reasoning for higher-dimensional Ising model and get $J’ \sim b^{d-1} J$ with the dimension $d$. This seemingly trivial reason has an important implication. For $d>1$, the two fixed points we discussed before are all stable, which indicates that there must be an unstable fixed point, between $T=0$ and $T=\infty$, working as the source of RG flow (while the unstable ones acting like sinks). Such an unstable fixed point can be identified as critical point. Even now, without any knowledge of the free energy, we should be able to figure out some critical, but, this is not our primary aim here. We will develop a more general theory for the fixed point concepts and study the short-range Ising model systematically to get all aforementioned critical exponentials.

Assume we have a RG transformation acting on a collection of coupling constants ${ K }$ as ${ K ‘} = R({K})$. We linearize this transformation near the fixed point ${ K^*}$

$K_a’-K_a^* \sim \sum_b T_{ab} (K_b - K_b^*),$

where we presume the GR transformation is differentiable and $T_{ab} = \frac{\partial K_a’}{\partial K_b} \vert_{K=K^\ast}$. Now we define the scaling variable $u_i = \sum_a \phi_a^i (K_a-K_a^\ast)$ and $\phi_a^i$ and $\lambda_i$ (or $\lambda^i$) are eigenstates and eigenvalues of the matrix $T_{ab}$ respectively. One can readily write down the transformation law for $u_i$

$$\begin{align} u_i’ &= \sum_a \phi_a^i (K_a’ - K_a^*) \ &= \sum_b \lambda_i\phi_b^i (K_b - K_b^*) \ &= \lambda^i u_i \end{align}. $$

In general, one can define quantities $y_i$ by $\lambda^i = b^{y_i}$

and $y_i$ are referred as RG eigenvalues. It can be distinguished as

i) $y_i>0$, then $u_i$ is relevant: RG transformation may drive it away from fixed point,

ii) $y_i<0$, then $u_i$ is irrelevant: RG transformation pulls it back to fixed point,

iii) $y_i=0$, then $u_i$ is marginal: it is undetermined by our current analysis.

For Ising model, if one study the geometry nearby the fixed point in a subspace spanned by two coupling constant ${K_1, K_2}$, it is clear that one of the parameters $K_1$ should be even (temperature-like and thus, referred as thermal scaling variable), while the other must be odd (magnetic scaling variable). The evenness or oddness is define through the spin flip symmetry $s \to -s$. Note that, these actually correspond to the two factors that drive phase transition in Ising model, that is, the temperature and external magnetic field. Now, we can classify the all the eigenvalues of our RG transformation into three group: a relevant thermal scaling variable $u_t$, a relevant magnetic scaling variable $u_h$ and an infinite set of irrelevant scaling variables. Suppose that all $u_i$ are analytic and must vanish at $t=h=0$, we have

$u_t = t/t_0 + O(t^2, h^2),~u_h=h/h_0+O(th).$

Similarly as we did for 1D situation, the free energy density (free energy per site) is

$f({K}) = g({K}) + b^{-d} f({K’}),$

As we discussed before, the $g({K})$ term comes from short-wave degrees of freedom and plays no role in our problem of interest. This gives us a homogenous transformation law for the free energy $f({K}) = b^{-d} f({K’})$. After some computing, we finally come to the rescaling behavior of free energy

$f(u_t, u_h) = \vert u_t/u_{t0}\vert^{d/y_t} f(\pm u_{t0}, u_h\vert u_t/u_{t0}\vert^{-y_h/y_t}),$

where $\vert b^{ny_t}u_t\vert=u_{t0}$ and $n$ is the time we repeat the RG transformation. This can be simplified by replacing $u_t$ and $u_h$ by $t$ and $h$

$f_s(t,h) = \vert\frac{t}{t_0}\vert^{d/y_t} \Psi \left( \frac{h/h_0}{\vert t/t_0\vert^{y_h/y_t}} \right),$

and $\Psi$ is a general scaling function. Following by this scaling law for

free energy, we can extract the critical exponentials with easy:

i) specific heat $C = \partial^2f/\partial t^2\vert_{h=0} \sim \vert t\vert^{d/y_t-2}$ gives $\alpha = 2 - d/y_t$,

ii) spontaneous magnetization $M_0 = \partial f/\partial h\vert_{h=0} \sim (-t)^{(d-y_h)/y_t}$ gives $\beta=(d-y_h)/y_t$,

iii) susceptibility in zero field $\chi = \partial^2 f/\partial h^2\vert_{h=0} \sim \vert t\vert^{(d-y_h)/y_t}$ gives $\gamma = (2y_h-d)/y_t$

iv) magnetization near critical point with non-zero magnetic field $M = \frac{\partial f}{\partial h} = \vert\frac{t}{t_0}\vert^{(d-y_h)/y_t} \Psi’ \left( \frac{h/h_0}{\vert t/t_0\vert^{y_h/y_t}} \right)$. For $M$ to be finite when $t \to 0$, $\Psi’(x)$ must have the form like $x^{d/y_h-1}$ when $x \to \inf$. This gives $M \sim h^{d/y_h-1}$ at $t=0$ and thus, $\delta = y_h/ (d-y_h)$. All the critical exponential we studied can be expressed as a function of the two RG eigenvalues and of course, the dimension $d$. If we do some algebra here, we can even find that

$\alpha + 2\beta + \gamma = 2,~\alpha+\beta(1+\delta)=2$.

Previously, when we use MFT to study the Ising model, we conclude that $\alpha=0$, $\beta=1/2$, $\gamma=1$ and $\delta=3$. Inserting all those numerics into the identity we just found, one may find that those identity are indeed satisfied. One may find that those results are independent of the rescaling factor $b$. It should be this way as the physics should not be affected by the way one rescales the system. However, from a mathematical point of view, the choice of $b$ does have influences on the expression of the transformation matrix $T_{ab}$ and thus, its eigenvalues and eigenstates. This dilemma can be eliminated as such. Any transformation can be generate by an infinitesimal transformation $b=1+\delta l, \delta b \ll1$. Then, the coupling constants transfer like (to 1st order)

$K_a \to K_a + \frac{dK_a}{dl} \delta l,$

where $\frac{dK_a}{dl} \delta l = -\beta_a({K})$ and $\beta_a$ is RG beta function (similar with the one in QFT). Now, the fixed points are just zeros of the beta function and $T_{ab}=\delta_{ab}+\frac{dK_a}{dl} \delta l$, giving its eigenvalues as $1+y_i\delta l$. Thus, its property totally determined by the nature of the generator of transformation with $b$, not $b$ itself.

Conclusion

In this term paper, we mainly study two different approaches, MFT and RG, to study critical behavior, with emphasize on the latter one. As we did in class, I incorporate the simplest Ising model to illustrate how those two methods work and how to use them to extract the critical exponentials. A relatively general formula for RG is discussed as well.

Acknowledgement

I thank Dr. H. Hu for helpful discussion.

Reference

Pathria, Raj Kumar. “Statistical mechanics.” (1972).

Cardy, J. L. “Scaling and Renormalization in Statistical Mechanics.” Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 392 (1996): 397.

Jaeger, Gregg. “The Ehrenfest classification of phase transitions: introduction and evolution.” Archive for history of exact sciences 53.1 (1998): 51-81.

Pfeuty, Pierre. “The one-dimensional Ising model with a transverse field.” ANNALS of Physics 57.1 (1970): 79-90.

Yang, Chen Ning. “The spontaneous magnetization of a two-dimensional Ising model.” Physical Review 85.5 (1952): 808.

McCoy, Barry M., and Tai Tsun Wu. The two-dimensional Ising model. Courier Corporation, 2014.

Kadanoff, Leo P. “Spin-spin correlations in the two-dimensional ising model.” Il Nuovo Cimento B (1965-1970) 44.2 (1966): 276-305.

Beyond mean field theory: the renormalization group idea